Spotlight: University of Ghana

Posted in News Story | Tagged Africa, ghana, news story

Study Abroad at the University of Ghana: A Precious Opportunity to Immerse in Anti-Colonial World-Making in the Global South

Written by Akanksha Sinha, SFS ’23

Akanksha (AK) Sinha is a Class of 2023 graduate of the Walsh School of Foreign Service. Akanksha majored in Culture and Politics with a focus on Post-Colonial Politics and Literature, and minored in Philosophy and Spanish. They studied abroad at the University of Ghana in Legon, Accra, during their Senior fall, Fall 2022. This article is their follow-on project as a Gilman Scholar.

Huanani Kay Trask, an Indigenous Hawaiian scholar and activist, states in her piece ‘Feminism and Indigenous Hawaii Nationalism’ that “theories hatched in universities… have only theory-making as their praxis.” When I first read this quote, I had to consider my own position as a student studying theory after theory in my college education, detached in many ways from the real world; it can become easy to forget that theories have material groundings and impacts. Especially in my field of study, which is post-colonial politics and literature, gaining theoretical knowledge is emphasized because it broadens our understanding of the world. At the same time, I pondered, what responsibility do we have, as students with privileged access to literature from across the world, to the physical spaces and communities that produce that very literature?

My interest in (so-called) ‘post-colonial’ politics and literature stemmed from growing up in India, where the legacies of colonialism physically and politically dominated the space. Some of examples of what I observed & experienced are: colonial-era monuments that remained some of our hottest tourist destinations; colonial land reclamations that doomed my city, Mumbai (once a series of islands among mangroves) to perpetually deadly flooding every monsoon season; colonial-era anti-LGBTQ laws that criminalized homosexuality and deepened India’s AIDS crisis; a colonial-era political system maintained by the same communities in power that prevented true decolonization and liberation for India’s most marginalized communities and castes; a drain of both resources and educated citizens from the country in search of employment and economic opportunity, leading to a deeply-entrenched caste & class system, abject poverty, and massive wealth inequality. In short, colonialism has shaped, and continues to shape, the lived realities in the Global South, and continues to necessitate the subjugation of the oppressed classes in order to keep the wheels of the neoliberal world model turning.

By my senior year, I decided that I wanted to study abroad, and more importantly, I wanted to study somewhere that could make systems of colonialism and neocolonialism more evident to my eyes. In a graduate-level class with Professor Olufemi Taiwo called “Philosophy of Colonialism”, I read powerful works such as Violence Over the Land by Ned Blackhawk, Family Matters by Nkiru Nzegwu, and finally, Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism by Kwame Nkrumah. Nkrumah’s book left a lasting impression on me, and it remains one of my top recommendations to anyone hoping to deeply understand neocolonialism. One thing about Kwame Nkrumah – he comes with RECEIPTS! This book relied on extensive evidence of banking, commerce, governance, and international systems, and the ways in which they are structured to commit blatant theft from former colonies. This book in particular helped solidify my decision to study in Ghana, in order to understand the material conditions that produced that book, the revolutionary action towards independence, the current struggles for liberation in the country, and the colonial hierarchies of labor and race that linked Ghana and India throughout our colonial eras and into our post-colonial century today.

Several aspects of studying in Ghana, rather than in any part of the imperial core, showed me that I had made the right choice for me. To start with, my classes began with the discussion of reparations for colonialism and slavery as a foundation to the rest of the semester. This was unlike most of my educational experience in the United States, where the question of reparations has largely remained a debate, with arguments surrounding the ‘why’ of reparations instead of focusing on the ‘how’ of making reparations possible. This was a welcomed shift in my education, and set the tone for the rest of the semester. Imagining a different future, in which we build a new world order on the premise of equality and the protection of the most marginalized and vulnerable among us, was not a passive exercise, but an active method for survival and resistance. As Mariame Kaba puts it, “hope is not a feeling but a discipline”, and starting in classrooms with reparations as the foundation is a powerful form of practicing hope as a discipline.

I also had the phenomenal opportunity of living and studying on the campus of the University of Ghana, Legon, Accra. My Politics of Ghana Since Independence professor, Prof. Lloyd G. Adu Amoah, shared with me the history of the university’s founding. The University came into being in 1948, after decades of agitation and organizing on the ground in various parts of West Africa, including the present day nations of Nigeria, Gambia, Sierra Leone and Ghana, to create opportunity for common people to pursue higher education even if they did not have the class resources to travel to the United Kingdom, which had been the only previous avenue for pursuing higher education. At first, the UK’s colonial governance set up the Elliot Commission to investigate this demand, and concluded with the idea of setting up a single university for the entirety of West Africa. The people of Ghana (then Gold Coast) rejected this inadequate proposal, and continued to resist, demanding a university for their people on their lands. The colonial response was that if the people of Ghana wanted this, they would have to fund it themselves. It was the ordinary people of Ghana, and in particular the cocoa farmers, who then raised the funds and set up this university. It is a testament to the power of the people. As I walked between our class buildings, libraries and dorms, I saw statues of farmers and buildings dedicated to the cocoa farmers who had brought the university to life. The university’s renowned degree in agriculture continues to honor the profession that has built its foundations. The university’s statues and architecture tell deep, complex stories of anti-colonial worldmaking in the 20th century, alliances and collaborations between newly independent nations and their people.

Witnessing this on the ground demonstrated to me the power of collective resistance to colonialism, the powers of the masses, the long-standing struggles for education and liberation, and the irreplaceable feeling of walking on such fertile ground for anti-colonial action. This is something that simply cannot be replicated in the imperial core, even if one is studying colonialism itself. The Balme Library on the University of Ghana’s campus held several rare books and archives from the last few centuries that are only available at that location. Although some of those may have copies in other places, many are too old and fragile to be digitized easily. I knew that the knowledge I was privileged to access at the University would not have been accessible to me on the internet. Our imperial core universities and their partnerships with websites to provide us with unlocked content can truly only go so far.

I quickly saw the on-ground impacts of colonial and neo-colonial extractivism. During my 5 months in Ghana, inflation rose rapidly, causing the prices of simple commodities such as eggs and rice to double, making it difficult for me to budget my scholarship money even week to week. By December 2022, my last month in the country, Ghana’s consumer inflation had soared to 54.1%, the highest in over 20 years. My experiences on the ground directly reflected what I was learning in my classes regarding the perils of economic neoliberalism on the Global South. Ghana remains crushed by debt traps, returning to the IMF more than 17 times since its independence, due to colonial legacies such as overdependence on few raw material exports (cocoa, gold), and the harmful neoliberal policies Ghana is forced to accept through the IMF, the World Trade Organization, ECOWAS, and other international bodies. My classes, and the like-minded Ghanaian, Nigerian, Haitian, and African-American people around me, imagined with me what this world could look like if reparational models of justice and protection of vulnerable populations guided our international frameworks instead of colonial, neoliberal worldmaking. I highly recommend the following works to help grasp these realities and explore that imagination further: Kwame Nkrumah’s, “Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism”, Ama Ata Aidoo’s “Our Sister Killjoy”, Olufemi Taiwo’s “Reconsidering Reparations”, Ayi Kwei Armah’s “The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born”, Walter Rodney’s “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”, and Max Liboiron’s “Pollution is Colonialism”.

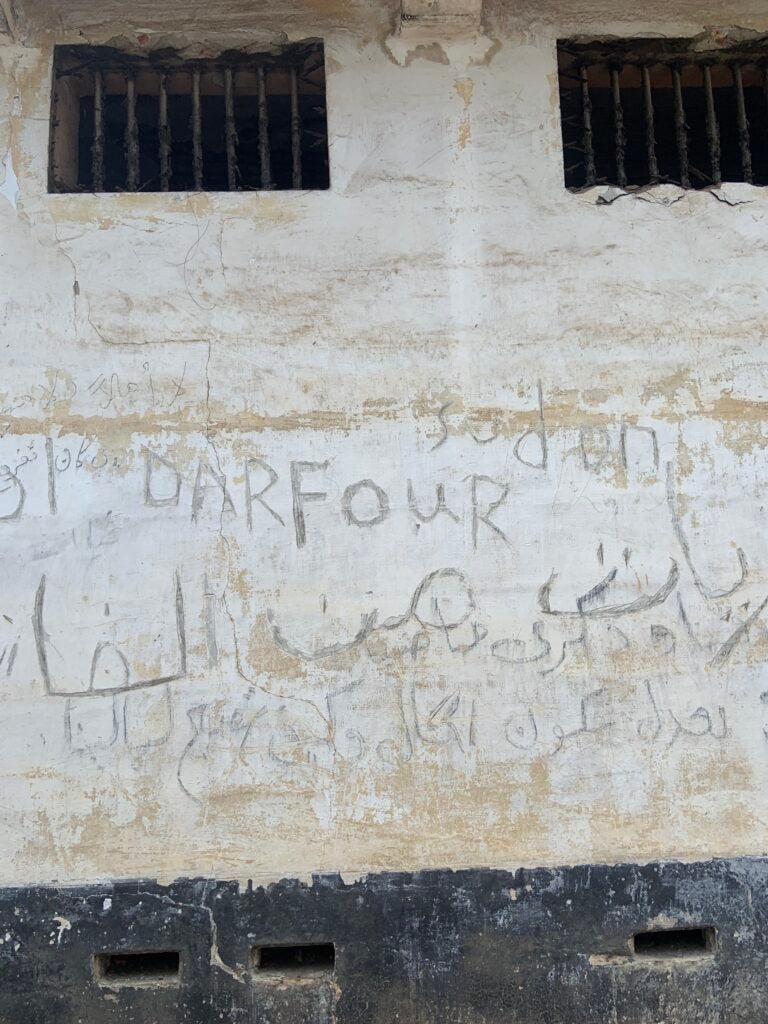

Moreover, I visited various historical sites as part of my classes and the CIEE Global Education program, and witnessed the gross underfunding that the Ghanaian governmental and non-profit organizations dedicated to the preservation of history were subjected to, leading to disrepair. This brought up a fundamental question of who in this era has the right to preserve history and tell stories; while museums in the imperial core are funded well enough and continue to hold on to artifacts stolen from Ghana, India, and the rest of the Global South, the Global South does not receive the funding to tell these histories on their own terms, or see the repatriation of their own artifacts, or receive reparations for having those articles stolen and used to generate interest and profits in the imperial core for decades. A tragic and striking component of my visit to Ussher Fort in Accra for example, was not just the small room dedicated to telling the story of this significant and tragic location [in comparison to the huge and sprawling museums I have seen in the West], but in fact the fresh writing on the walls from recent refugees from Sudan. This colonial site of enslavement and the export of enslaved Africans had then turned into a jail during the colonial period and remained so until 1993, and now was a passing port for the refugees being displaced due to neocolonial extraction and conflict unfolding across their lands. It was important to me that I bore witness to this, and to the severe dehumanization and human cost of the neocolonial world order. How much tragedy, blood, bones, death, rape, family separation, and destruction of humanity was held within these walls? It was overwhelming to stand on this ground. It was beyond heartbreaking to tread the routes of enslaved African peoples from centuries ago, and then know these same routes were tread by the Black, Sudani refugees of today. Such experiences imbue clarity and unshakeable commitments to humanity as we connect the dots and struggle for a liberated world.

In Ghana, I was able to engage deeply with anti-colonial worldmaking in practice, and witness the impacts of the global, hierarchical legacies of power left by colonialism and upheld by neocolonialism. I also had the opportunity to meet some Indian communities in Ghana, and explore the racial hierarchies that had facilitated the transfer of Indian, Lebanese, and other non-Black communities to Ghana as merchants, traders, and business-owners especially post-Independence. White individuals of the colonial class sold their properties and businesses only to non-Black peoples as they exited, or only patronized the businesses and properties of those with more proximity to whiteness. The Indian experience in the area was significantly different from the Indian experience in places such as Kenya, South Africa, and the Caribbean. In Ghana, most Indians had come during colonial and post-colonial times from places such as Gujarat, where many Indian mercantile and trading families are from, rather than states such as Bihar, from where indentured labor was taken to Guyana, Trinidad & Tobago, and other parts of the Caribbean; or Punjab, from where manual laborers were taken to Kenya and South Africa to work alongside Black African laborers to construct railways and other colonial apparatuses. Today, some of the largest department stores in Ghana are Indian-owned, while many of the expensive, upper-class establishments in downtown Accra are Lebanese-owned. At the same time, illegal mining, in which private Chinese citizens and Chinese businesses are implicated, continues to displace Ghanaian peoples and exploit Ghanaian labor. Anti-Blackness remains the foundation of today’s world order, and solidarity across race, class, and gender is vital to building a just and equitable world for tomorrow.

Visits to sites that invited me to bear witness to realities of dehumanization over the centuries were interwoven with sites of resistance, rejuvenation, and commitment to a just future. I got to see WEB Du Bois’ home, resting place, and library, a site of huge cross-Atlantic significance and reconnection. I went to art shows where young, imaginative, and bold Ghanaian artists showcased their works, and I appreciated many, many powerful murals reclaiming cross-Atlantic histories and Ghanaian efforts of resistance. I got to see Stonebwoy, Tems, Stormzy, Sarkodie, Gyakie, Usher and my long-time fave, SZA live in concert while attending the Global Citizen concert in Accra! I witnessed the entirety of the crowd boo in unison when President Akufo-Addo came out to give a speech at that same concert, and felt the fervors of grassroots political mobilization throughout the semester. I ate such a diverse variety of foods, from goat soup and fufu to grilled fish and banku to bofrot nearly every morning before class, and I can truly say I loved every new food experience. I have a deep love for food and will try any dish at least once! Traveling through Ghana’s many different regions allowed me to experience a delectable diversity of flavors. While visiting Kumasi with a friend, I attended the Manhyia Palace Museum for the Akwasidae festival on Christmas Day, celebrated by the Ashanti chiefs and peoples. The CIEE Study Abroad staff took our cohort on a three-day weekend visit to the Volta River, where I kayaked in beautiful, cool waters, learned from village community members about the art and heritage of pottery in the region, and immersed myself in more of Ghana’s powerful, breathtaking natural landscape.

My study abroad experience at the University of Ghana continues to shape my work and life post-graduation. There is a certain depth of experience I was privileged to receive when studying amongst other colonized peoples, on colonized lands, and being able to draw those systemic understandings to my life in India and now in the United States. I highly encourage students to consider studying in Ghana, and also in other places in the Global South, as an opportunity to push past comfort zones, stand on hallowed, revolutionary land, and firmly ground any political theory or framework in the realities of people actually living with the consequences of our current world-making. The learning is immeasurable. The urgency of a new, equitable, just world is brought to the forefront, as is the disciplined optimism needed to make that world possible.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- Resources for further education as you prepare to engage responsibly with study abroad in the Global South

- How Not to Study Gender in the Middle East

- Studying Abroad: An Anti-Colonial Inquiry

- How to Decolonize Your Education Abroad Experience (and What It Means)

- To diversify study abroad, we must decolonize it

- Connected Understanding: Internationalization of Adult Education in Canada and Beyond | University of Stirling

- (PDF) Decolonization and Knowledge Inequalities: Towards a pluriversity of approaches, including participatory research

- View of Global Education from an ‘Indigenist’ Anti-colonial Perspective

- Some of my class projects during my study abroad at the University of Ghana

- Some pictures from my study abroad experience!